Penguins in a state of ecstasy: SCIoI researchers use event cameras to shed light on a strange behavior shown by Antarctic penguins

Penguins exhibit a common but bewildering behavior in which they stand up tall, look up to the sky, flap their wings, and let out a loud call. Experts call it “ecstatic display.” A team of scientists from the Science of Intelligence (SCIoI) Cluster of Excellence at TU Berlin, the University of Oxford, and Oxford Brookes University has broken new ground in research to explain this behavior. Their hypothesis is that the ecstatic display is a type of territorial behavior that is mostly seen when a penguin has to wait a long time for its mate to return. The team discovered this with the help of the novel concept of event cameras. Unlike traditional cameras, event cameras do not capture entire images in one shot; instead, they record changes in brightness, i.e. the events, for each pixel separately. Alongside a myriad of other potential applications, event cameras can significantly facilitate and improve wildlife observation.

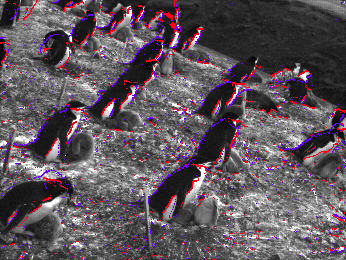

It’s an hour-long trek from the Spanish research station on Deception Island, located in the north of the Antarctic continent, up to Punta Descubierta. As its Spanish name suggests, it is a rocky ridge exposed to the elements and sparsely covered with algae. But it is nonetheless home to a colony of chinstrap penguins, who populate Antarctica in generous numbers. “There’s a total of around 20,000 animals living there, who are undeterred even by the frequent gusts of over 100 kilometers per hour,” says Dr. Ignacio Juarez Martínez of the Department of Biology at the University of Oxford.

Previous research refuted

Dr. Juarez Martínez investigated the behavior of chinstrap penguins in his doctoral thesis, and the strange phenomenon of ecstatic display was one of the things he wanted to understand more about. “One of the few studies on the topic looked at Adélie penguins, a relation of the chinstrap, and claimed that only males showed the ecstatic display, and primarily did so during the Antarctic spring in October. The researchers therefore assumed that it might be a mating ritual. We were able to prove this theory wrong.”

© Ignacio Juarez Martínez

Science of Intelligence unites researchers

Ignacio Juarez Martínez enjoyed one of those remarkable coincidences in science that happens when researchers from different disciplines come together. The Science of Intelligence Cluster of Excellence at TU Berlin promotes exactly this scientific exchange by bringing together researchers from over 12 disciplines to investigate the principles of intelligence. “One of Ignacio’s doctoral supervisors, Professor Dr. Alex Kacelnik, is a head researcher exploring the intelligence of animals in the cluster,” says Friedhelm Hamann, doctoral student at TU Berlin. “He got into conversation with my doctoral supervisor there.” Hamann’s supervisor, Professor Dr. Guillermo Gallego, heads the Chair of Robotic Interactive Perception at TU Berlin and is also a member of the Cluster of Excellence. As part of his research into new perception systems for robots, Gallego has significantly advanced the technology of event photography. Gallego and Kacelnik both recognized the potential of event cameras for wildlife observation, and so the collaboration between their doctoral candidates took flight.

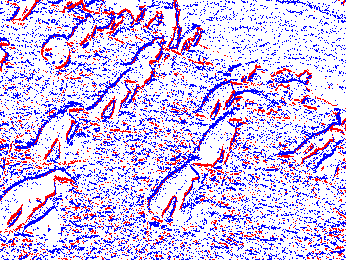

Event photography works without exposure time

Event photography is inspired by human vision: Similar to the way the retina functions, each light-sensitive pixel in the camera contributes at different times to the overall image; this means there is no exposure time following which all pixels are read at once. As the pixels only send a signal when the intensity of the incident light changes, event cameras use relatively less energy. What’s more, because there is no exposure time for the camera to decide on, both dark and bright areas can be depicted almost equally well. Event cameras thus perform very well in poor lighting conditions. Again, since they do away with exposure time, event cameras also boast a shorter reaction time. This makes it easier to analyze quick movements, such as a penguin flapping their wings.

Footage from event cameras analyzed using machine learning

“Through comparative tests, we determined that the event camera used for the project consumes five times less energy than a conventional camera,” reports Friedhelm Hamann. “Combined with good image quality in low light conditions, this feature makes the event camera ideal for use in remote locations such as our penguin colony. We were able to observe the animals almost continuously.” Sixteen nests were filmed for several weeks during the nesting season. The researchers then examined 24 ten-minute video sequences and tagged the points at which a penguin showed the ecstatic display. “It happens surprisingly often, around 20 times an hour,” says Hamann. These tagged video sequences were used to train algorithms that could then extract footage with ecstatic displays from the total material. “These algorithms were originally developed for games consoles to detect player’s movements,” explains Hamann.

Ecstatic waves roll through the penguin colony

In addition to these computer analyses, blood samples were taken from the penguins to determine their sex, as there is no way to determine if they are male or female visually. “Our investigations revealed that both male and female penguins show the ecstatic display with the same frequency. Since we observed the penguins outside the mating season, it cannot be a mating ritual,” confirms Ignacio Juarez Martínez. Instead, the scientists found that the ecstatic display is virtually contagious; penguins in the near vicinity feel compelled to join in. “This can actually cause a kind of ecstatic wave to run through the entire penguin colony,” says Juarez Martínez.

© Ignacio Juarez Martínez

Ecstatic display when waiting for mate

What’s much more interesting is the fact the longer each penguin has to wait for its mate, the more often it performs the ecstatic display. “Penguins take turns during the incubation period and share parental duties when the chicks hatch. One will be sitting on the nest while the other takes to the ocean to hunt for krill. The parents regurgitate their stomach contents to feed the young birds,” says Juarez Martínez. At feeding time, the number of ecstatic displays increases exponentially the longer it has been since the last changing of the guard. “Especially after the sixth hour, when a penguin’s mate should really have already returned, the prevalence increases dramatically.” Why they do so is still unclear to the researchers. They think it plausible that it is some kind of territorial behavior, and want to use this working hypothesis to conduct further research.

Wide range of applications for event photography

“The high information value of the data collected with the event camera was what helped us study the ecstatic display in such detail,” says Juarez Martínez. The scientists at the SCIoI Cluster of Excellence at TU Berlin have arranged further projects with wildlife researchers. One example is using the event camera to analyze bird behavior. “The camera’s fast reaction time is particularly advantageous here, as it allows extremely slow-motion shots,” says Friedhelm Hamann, who is enthused about these new applications. “Event cameras have the potential to help robots see, increase the safety of self-driving cars, and analyze industrial processes. Large chip manufacturers are even working to build them into smartphones. The fact that we can now also support behavioral research shows how versatile this new technology is, and just how interdisciplinary the research here at the SCIoI is.”

© SCIoI/ Friedhelm Hamann

Further information

The research project was supported by the Oxford Berlin Early Career Mobility Program of the Berlin University Alliance (BUA), the Alliance of Excellence of FU Berlin, HU Berlin, TU Berlin, and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The funding made it possible for Ignacio Juarez Martínez to spend several weeks working at the Science of Intelligence Cluster of Excellence.

The investigations of the research team (Friedhelm Hamann, Suman Ghosh, Ignacio Juárez Martínez, Tom Hart, Alex Kacelnik and Guillermo Gallego) were published as a main conference paper at the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2024 (17–21 June 2024), the world’s most prestigious conference on machine vision.