Seeing the future: how expectations guide eye movements

Eye movements are the human body’s fastest and most common actions: We actively shift our gaze about two to three times per second to gain information about our environment. Where we look determines what we learn about the ever-changing world around us. On the other hand, what we know and what we expect to happen in the world also impacts the way we move our eyes. A study published in Psychological Science by Nicolas Roth, Jasper McLaughlin, Klaus Obermayer, and Martin Rolfs from the Cluster of Excellence “Science of Intelligence” (SCIoI) in Berlin reveals how our expectation of what might happen next in a scene shapes our gaze behavior.

How we explore real-world scenes

Imagine you see a cat behind a window. Even if the cat is standing still at the moment, you are probably curious about what it’s going to do next, and since you don’t want to miss any action, you are likely to keep your eyes fixated on the animal. In comparison, if you’re looking at a picture of the same scene, you already know the cat won’t move, and therefore know you won’t miss anything, so after a brief glance at the cat, you will probably continue to explore the rest of the room. While this example may intuitively make sense, only little is known about how knowledge and expectations influence our exploration behavior.

Psychological studies investigating how we explore our environment typically use static images as a substitute for the real world around us. Hence, they cannot tell us anything about how we react to (possible) changes in our field of view. Existing research on dynamic scenes has attributed differences in our exploration of videos compared to images to the actual movement of objects, but up until now scientists had never explored how a person’s expectation about changes in the scene can influence our gaze.

Isolating the “potential for change” from actual scene changes

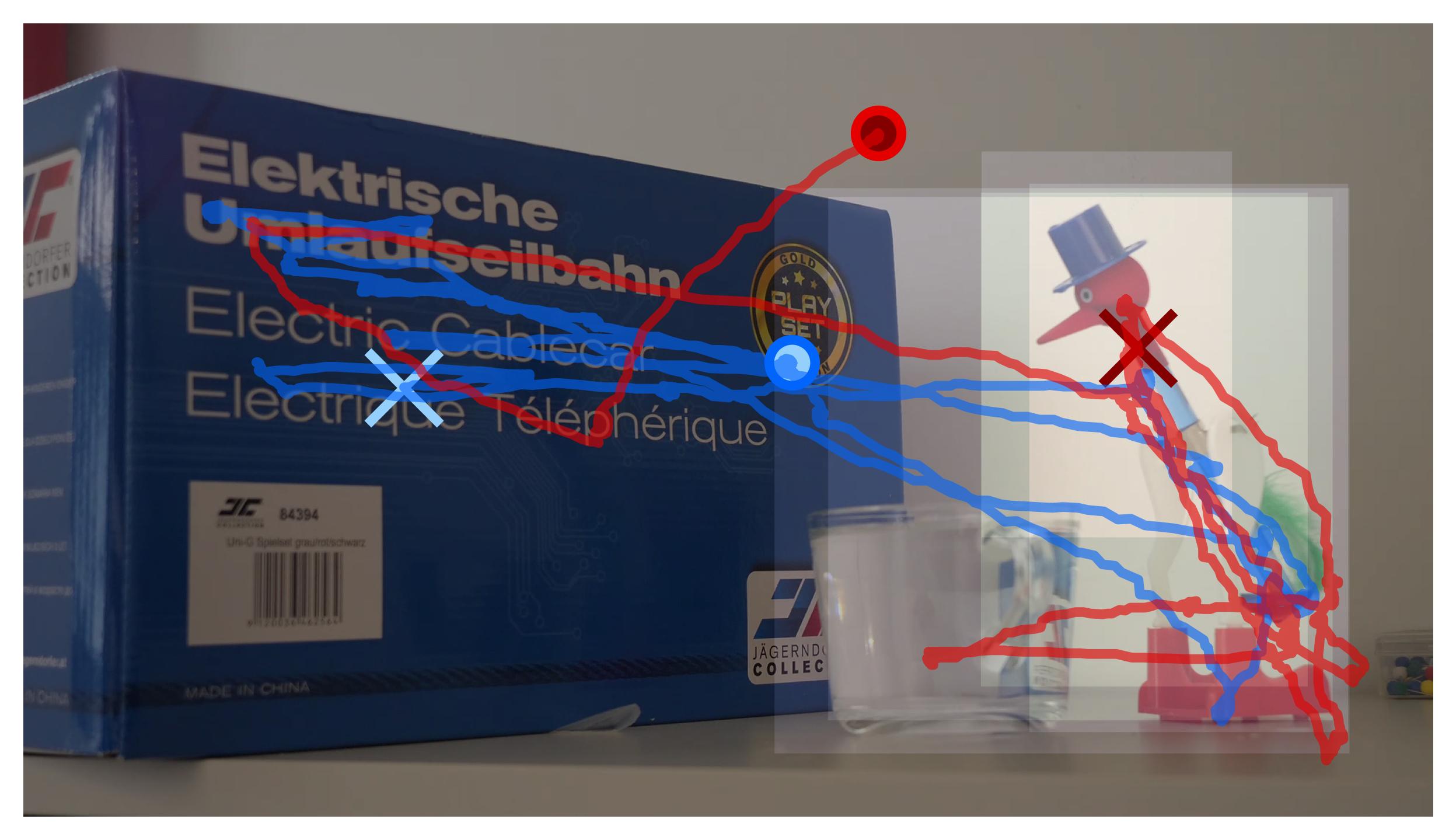

In order to understand how the “expectation factor” influences our eye movements, the researchers showed real-world scenes—including cats, traffic, toys, and other everyday situations— to twenty healthy adult participants, either as static images or as dynamic videos. To be sure to only investigate the effect of the expectation and not of the actual scene changes, the scientists used an experimental design consisting of two conditions: in the so-called “static image” condition, the participants were shown the static scenes for ten seconds, while in the “unfreezing video” condition the same scenes were shown as frozen (i.e., static) for the first five seconds (and were hence identical to the images in the “static image” condition), before “unfreezing” and playing for another five seconds as dynamic videos. The participants saw scenes from both conditions in a random order, but they were always informed in advance about the condition they were about to see, which created different expectations.“It is important to note that for our results, we only analyzed the data from the first five seconds, the period in which both conditions presented identical non-moving images. The participants knew whether or not the scene would turn into a video, and based on this expectation alone, they showed insightful differences in their eye movement behavior,” explains Nicolas Roth, the study’s lead author.

By tracking the locations the participants looked at, the researchers discovered that in the case of the “frozen videos,” people’s eyes are drawn to areas with a high “potential for change” (PfC)—objects or locations in the scene where movement or other changes can be expected—even before any movement is present. “Our study shows that even when our world appears to be static, the mere thought that something might change will keep our brain on the lookout for possible changes. This is a crucial part of how we interact with our dynamic world,” said Roth. “It probably doesn’t come as a surprise that our expectations influence our viewing behavior. But through this design, we can, for the first time, really investigate this effect in natural scenes.”

A universal effect

The research demonstrated that this behavior is not limited to animate objects like people, cats, or other animals. And while it has been argued before that keeping track of other animals is especially relevant for our survival, inanimate objects, like traffic lights, screens, or unstable towers, also lead to similar gaze patterns. This new “potential for change” metric, developed by the SCIoI researchers, explains differences in gaze behavior more effectively than established measures such as whether an object is animate or how salient or prominent it is.

This insight has significant implications for the Science of Intelligence cluster, whose aim is to understand natural intelligence in order to build intelligent machines. “If we want to develop machines that can explore the world like humans, we have to understand what information humans use from our environment. Our results show that such expectations about potential scene changes play an important role in that,” says Roth. “Since this effect was so strong and robust in our healthy adult participants, we have now started to measure how this behavior is affected by age and neurological conditions, like Parkinson’s disease.”

In summary, the study shows that our eyes are guided by what we expect to happen, revealing a deeper layer of how we perceive and interact with the world. This discovery not only advances our understanding of human cognition but also opens new avenues for creating smarter technologies and diagnostic tools.